PLEASE READ "WHY MY BLOG" IN THE BLOG ARCHIVE... The judge at my sentencing gave me this blessing: "...I would like to state my special appreciation to all the people who have written letters detailing Rabbi Mintz's entire life in so many ways. It really gives me the full picture of his remarkable Rabbinical career and the depth of gratitude that so many have toward him for his long years of service. I have no doubt his service, in different forms, will continue as long as he is on this earth."

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Letter 5 to rabbi Juda Mintz

The following letter was written to Rabbi Juda/Yehuda Mintz from Mark, a Jewish inmate at the Fort Dix Penitentiary...

Juda,

You are an inspiration to me. Watching the quiet way you keep services in task, while adding so much by introducing us to new songs and new styles of the traditional prayers. Bringing singing into the services is, in my eyes, your greatest gift to us. To hear the group singing with your voice carrying the tunes.

You are willing to help and teach anyone, anywhere. Without a doubt, the Sunday we arrived for a Hebrew lesson to find our usual room filled with Muslims cleaning up after a breakfast meeting. Within a few moments of our arrival, you changed a tense atmosphere into one of peace and brotherhood. Using a quiet and unassuming way, you got them talking and the line from the "Grace After Meals", "May the Merciful One create brotherhood between the children of Issac and the children of Ishmael."

Weeks later I am still being called brother by Muslims who were there that Sunday morning.

I will always cherish the memory of our time together. My thoughts will be filled with lessons from the Torah studied with you and watching the way you interact with people.

Hashem blessed me with your presence in my life.

-George

Juda,

You are an inspiration to me. Watching the quiet way you keep services in task, while adding so much by introducing us to new songs and new styles of the traditional prayers. Bringing singing into the services is, in my eyes, your greatest gift to us. To hear the group singing with your voice carrying the tunes.

You are willing to help and teach anyone, anywhere. Without a doubt, the Sunday we arrived for a Hebrew lesson to find our usual room filled with Muslims cleaning up after a breakfast meeting. Within a few moments of our arrival, you changed a tense atmosphere into one of peace and brotherhood. Using a quiet and unassuming way, you got them talking and the line from the "Grace After Meals", "May the Merciful One create brotherhood between the children of Issac and the children of Ishmael."

Weeks later I am still being called brother by Muslims who were there that Sunday morning.

I will always cherish the memory of our time together. My thoughts will be filled with lessons from the Torah studied with you and watching the way you interact with people.

Hashem blessed me with your presence in my life.

-George

Letter 4 to Yehuda Mintz

The following letter was written to Rabbi Juda/Yehuda Mintz from Richard, a Jewish inmate from Fort Dix Penitentiary...

Dear Juda,

As I am now preparing to leave this institution, before doing so I want to share some of my feelings with you regarding our relationship.

Although I have only known you for a relatively short period of time, you have made a profound impression on me and I am most grateful for having had the opportunity to make your acquaintance.

I'm certain that you have amassed an impressive list of achievements and have had a positive influence on the religious lives if many people throughout your many years as a pulpit rabbi. You are a very warm, candid and sincere person to whom people can easily relate and in whom people can easily trust. Unfortunately, I have no personal experience or knowledge of your pulpit achievements; I can only imagine how effective you were.

However, from what I've observed and learned about you in our brief period of acquaintance, I know that you are an exceptional individual. I consider it a personal honor to be able to say that I know you and consider you to be amongst my good friends. You have demonstrated some unique attributes that clearly differentiate you positively from others.

One of the things that impressed me most about you was your ability to communicate effectively with many diverse elements. You were not deterred by any pre-existing strife and managed to relate well with all elements. In an environment in which many people exhibit zeal and fanaticism, you stood out as the one who would tolerate all views and still maintain your sound religious convictions. At the time we first met, I myself had taken a firm position in this polarized community. However, soon thereafter, I realized the importance of tolerance and moderation. Your interpersonal skills are truly extraordinary!

I've also been most impressed with your leadership ability. Although you are not the dynamic politician who will stand on a soap box and rally people to a cause, you are very effective in getting things done and introducing innovative ideas. It's interesting to note that all diverse elements within the community have recognized and accepted your leadership. You've enriched our religious services with the introduction of more singing. More significantly, you've introduced a regular class (Ethics of the Fathers-Pirke Avot) which has been gaining an increasing following every week. This class is much more than an opportunity to sit together, learn and discuss topics. The subject matter deals directly with how we lead our lives. What are the behavior patterns and goals that we should strive for? What are the pitfalls to avoid? I can think of no discussions that are more important to this community then the above ethics. Yet, until you took the initiative, these discussions were non-existent here!

After your arrival here, people got to know you know you quickly. In a very short time you gained the trust and respect for others. This respect was not based on your prior achievements, but based on the type of person you are. I perceive you as the "mild mannered rabbi" who is understanding and compassionate to all yet still steadfast in your religious conviction and dedication to service others.

I take pride in stating that you were one of my friends here. I hope that our paths will cross again some day in the future. I pray that G-d grant you the strength and wisdom to succeed in any future endeavors. I know that you have the skills and dedication to bring any project to successful fruition.

Please never hesitate to call on me if I can help you in any way.

With deepest feelings of brotherhood,

Richard

A COPY OF THE LETTER BELOW...

Dear Juda,

As I am now preparing to leave this institution, before doing so I want to share some of my feelings with you regarding our relationship.

Although I have only known you for a relatively short period of time, you have made a profound impression on me and I am most grateful for having had the opportunity to make your acquaintance.

I'm certain that you have amassed an impressive list of achievements and have had a positive influence on the religious lives if many people throughout your many years as a pulpit rabbi. You are a very warm, candid and sincere person to whom people can easily relate and in whom people can easily trust. Unfortunately, I have no personal experience or knowledge of your pulpit achievements; I can only imagine how effective you were.

However, from what I've observed and learned about you in our brief period of acquaintance, I know that you are an exceptional individual. I consider it a personal honor to be able to say that I know you and consider you to be amongst my good friends. You have demonstrated some unique attributes that clearly differentiate you positively from others.

One of the things that impressed me most about you was your ability to communicate effectively with many diverse elements. You were not deterred by any pre-existing strife and managed to relate well with all elements. In an environment in which many people exhibit zeal and fanaticism, you stood out as the one who would tolerate all views and still maintain your sound religious convictions. At the time we first met, I myself had taken a firm position in this polarized community. However, soon thereafter, I realized the importance of tolerance and moderation. Your interpersonal skills are truly extraordinary!

I've also been most impressed with your leadership ability. Although you are not the dynamic politician who will stand on a soap box and rally people to a cause, you are very effective in getting things done and introducing innovative ideas. It's interesting to note that all diverse elements within the community have recognized and accepted your leadership. You've enriched our religious services with the introduction of more singing. More significantly, you've introduced a regular class (Ethics of the Fathers-Pirke Avot) which has been gaining an increasing following every week. This class is much more than an opportunity to sit together, learn and discuss topics. The subject matter deals directly with how we lead our lives. What are the behavior patterns and goals that we should strive for? What are the pitfalls to avoid? I can think of no discussions that are more important to this community then the above ethics. Yet, until you took the initiative, these discussions were non-existent here!

After your arrival here, people got to know you know you quickly. In a very short time you gained the trust and respect for others. This respect was not based on your prior achievements, but based on the type of person you are. I perceive you as the "mild mannered rabbi" who is understanding and compassionate to all yet still steadfast in your religious conviction and dedication to service others.

I take pride in stating that you were one of my friends here. I hope that our paths will cross again some day in the future. I pray that G-d grant you the strength and wisdom to succeed in any future endeavors. I know that you have the skills and dedication to bring any project to successful fruition.

Please never hesitate to call on me if I can help you in any way.

With deepest feelings of brotherhood,

Richard

A COPY OF THE LETTER BELOW...

Letter 3 to Juda Mintz

The following letter was written to Rabbi Juda/Yehuda Mintz from Eli, a Jewish inmate at Fort Dix Penitentiary...

July 13, 2003

Dear Rabbi Mintz,

I hereby give you this letter, upon my departing the Federal Correction Facility at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

I cannot say nor elaborate in these few lines what my coming to know you means to me. Especially our nightly sessions of studying the famous works of "Duty of the Hearts".

I cannot say nor elaborate on your profound impact on the Jewish community here at Fort Dix. I was watching you in amazement, when in your weekly discourses and lectures, how you were able to relate to each and every inmate from such diverse backgrounds to find the proper approach to each individual.

May Hashem be with you, in all your future endeavors. One thing is for certain, just as a prophet is not allowed to withhold his prophecy, so you Rabbi Mintz are obliged to continue enlightening Jewish children for many years to come with G-D's help.

Your dear friend,

Eli

Letter 2 to Rabbi Yehuda Mintz

The following letter was written to Rabbi Juda/Yehuda Mintz from a Jewish Inmate in the Fort Dix Federal Penitentiary...

Rabbi Juda Mintz,

Dear Rabbi,

In the short time that I have known you, I have felt blessed with your wisdom and companionship.

Throughout these difficult fourteen years behind bars, I have never had a close relationship with a teacher with such wisdom and the highest of knowledge. My hope is that Hashem will give you more and more wisdom, as falling rain may fall as a blessing upon those whom are thirsty and in need of this highest of water from heaven.

Life has shown me, in some very difficult ways, and sometimes in incomprehensible forms, that we must go ahead to discover that we can leap if we can walk.

It's true; the same sun which is here showing us his wonderful light, the same star that you will see no matter where you are. May this Radiant Marvel spill over your congregation, and may the Blessed One grant you welcome in the middle of Israel soon.

From deepest within me, is my wish the Lord will bless you and keep yours; may the Lord show his favor and be gracious to you. May the Lord show you his kindness and grant you peace.

May your spirit and wisdom continue to sow the seeds of Love, and so may you harvest the food of hope which your community seeks. That the marvelous Tree of Knowledge continue extending its branches to the "Birds of Heaven" So that he may find shelter... That the "full moon" will cover your heart, and that every month becomes a promise of splendor and happiness.

Put Hashem and the blessing of His Angel before you to keep you safe and give you all his wonderful teaching . So that you may complete his wonderful teaching, so that you may complete your Radiant labor...

Hashem blessed you and all your new "herds" which is blessing with presence and great heart, that wonderful Tribe which will surely receive Milk and Honey as rain from the Highest...

May Hashem work marvelous wonders in your congregation and become like the Star of Israel.

Letter 1 to Rabbi Juda MIntz

The following letter was written to Rabbi Juda/Yehuda Mintz from a Jewish Inmate at Fort Dix Federal Penitentiary....

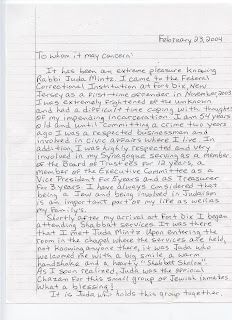

To whom it may concern:

It has been an extreme pleasure knowing Rabbi Juda Mintz. I came to the Federal Correction Institution at Fort Dix, New Jersey as a first-time offender in November 2003. I was extremely frightened of the unknown and had a difficult time coping with thoughts of my impending incarceration. I am 54 years old, and until committing a crime two years ago I was a respected businessman and involved in civic affairs where I live. In addition, I was highly respected and very involved in my Synagogue serving as a member of the Board of Trustees for 12 years, a member of the Executive Committee as a vice president for 5 years and as treasurer for 3 years. I have always considered that being a Jew and being involved in Judaism is an important part of my life as well as my family's.

Shortly after my arrival at Fort Dix I began attending Shabbat services. It was there that I met Juda Mintz. Upon entering the room in the chapel where the services are held, not knowing anyone there, it was Juda who welcomed me with a big smile, a warm handshake and a heartily "Shabbat Shalom". As I soon realized, Juda was the official Chazan for this small group of Jewish inmates. What a blessing!

It is Juda who holds this group together. In every sense Juda has been our Rabbi. He has been eloquent in leading Friday night Shabbat services and Saturday Torah readings and study. His continuous commentary has been instructional as well as thought provoking. His constant interpretation of the psalms during Shabbat services has demonstrated his sensitivity and compassion for his "congregation". Juda has introduced different melodies for many prayers and songs, explaining their origins. As we sing, it is his voice that rises above the rest in leadership. His voice will be sorely missed but I will forever hear it in my head. Juda's leadership during Torah Study has been incomparable. He carefully has explained the weekly Parsha and provokes highly intelligent discussion on its interpretation and meaning. He has shared with us many other scholars' writings on each Parsha. Juda also stays after each weekly Torah study or meets a few of us on Sunday mornings to help with our Hebrew reading. I have found this has greatly expanded my ability to read Hebrew at Shabbat services and Torah study. Juda is a skilled and patient educator.

For me, the traits that most exemplifies Juda's skills as a Rabbi have been on a personal level. Juda has been kind and compassionate in helping me deal with this most difficult time in my life. He is a good listener and always puts a positive spin on how we must make the best of this terrible situation. He is quick to point to passages in the Torah which have helped me realize that life will be better once I have dealt with this punishment for my sins. Juda has helped me with gaining a better understanding that we all learn from our sins and will be better persons someday. He has given me the ability to help my family deal with this situation.

Personally, I will greatly miss Rabbi Juda Mintz, but am very happy he will be leaving here to continue on with a most productive life for himself. I would be honored to someday have Rabbi Mintz as the spiritual leader of my congregation. He is a scholar, an educator and has pastoral skills that exemplify his care and compassion for his congregation.

Very Truly Yours,

Steven

Letters From Fellow Jewish Inmates of Fort Dix Federal Penitentiary

The letters above are written by fellow inmates who I was privileged to meet while I was incarcerated at the Fort Dix Federal Penitentiary.

Somewhat in the manner of Joseph from the Bible (Torah), who was incarcerated, albeit for different reasons, I too was able to teach Torah, the basic tenets of Judaism and to conduct Shabbat services.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Addiction is a disease

The following article discusses addiction as a disease. This is an explanation not an excuse to "use".

Contrary to the opinion of many, addiction is not a matter of the "Yetzer Harah"(The evil inclination).

Yehuda/Juda Mintz

Contrary to the opinion of many, addiction is not a matter of the "Yetzer Harah"(The evil inclination).

Yehuda/Juda Mintz

The most important question there is about addiction

A response by Dr. Kevin McCauley, M.D. to the article posted on Slate.com, "Medical Misnomer: Addiction isn't a brain disease, Congress"

The question of whether or not addiction is really a disease is the most important question there is about addiction, and the reputation of addiction medicine rests upon its ability to provide a coherent answer. One of the major projects at our institute is to investigate the possibility of such an answer.

Her odd association with an ultra-conservative think thank (The American Enterprise Institute) notwithstanding, Dr. Satel’s monograph “Is Drug Addiction a Brain Disease?” is the best-articulated argument against the conceptualization of addiction as a disease (it can be found at http://www.eppc.org/publications/bookID.19/book_detail.asp). Likewise, Dr. Lillianfeld’s effort to expose semantic mistakes in psychology is commendable. However their views on addiction reveal fundamental mistakes regarding the nature of addiction and the experience of the addicted patient.

On the question of language, the authors claim that characterizing addiction as a brain disease appropriates language used to describe conditions such as multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia. Yes, and rightly so. Our modern concept of disease – the “Disease Model” – emerged from Germ Theory over a century ago, and evolved such that today it can be defined as a physical, cellular defect or lesion in a bodily organ or organ system that leads to the expression of signs and symptoms in the patient. This is a very rigorous standard for disease (it is also the standard demanded by Dr. Thomas Szasz, another opponent of the conceptualization of addiction as a disease).

For most of the last century, it has not been possible to fit addiction to this standard. That has changed. The organ involved in addiction is the limbic brain (specifically the ventral tegmentum and nucleus accumbens/extended amygdala). The defect is a stress-induced/genetically predisposed dysfunction of the limbic dopamine system (specifically a hedonic dysfunction – a broken “pleasure sense”). And the symptoms of greatest importance are 1) loss of control, 2) craving, and 3) persistent drug use despite negative consequences. Addiction meets the standard definition of disease better than multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia, two diseases whose pathophysiologies are far less elucidated. This is why medicine can claim, with confidence, that addiction is a disease.

On the question of personal agency and choice, the authors complain that calling addiction a “disease” undermines personal agency and our concept of free will. This is not, however, a problem with addiction. The standard definition of disease as it is used in medical practice today strips patients of their power of choice and hands that power to the doctor. In exchange, the patient gets to enter the sick role – a helpless, compliant role, and one relieved of responsibility. So the problem of addicts claiming that they have a disease and must be absolved of responsibility for their behavior is not a problem with addiction. It’s a problem with our standard definition of disease. Most of the authors’ trouble in calling addiction a disease stems not from whether or not addiction fits our standard definition of disease (it does), it stems from the problems inherent in the Disease Model itself.

As for choice, in addition to being a broken hedonic system in the brain, addiction is also a disorder of volition. Craving states cause a selective hypofunctionality of the prefrontal cortex. This is visible on neuroimaging scans such as functional MRI. The area of the brain of particular interest is the ventro-medial prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain that assesses future consequences. It is hard to underestimate the importance of these findings. They imply that choice is a variable quantity during some brain disease states. The exciting opportunity here is to figure out how choice really works. How is it realized in the brain? What are the conditions under which it best operates? And how do we set those conditions so that addicted patients can exercise free will according to their true values?

The authors may be correct in their assertion that these neurological scans may not mean all that their proponents say they do. But they do mean something. At the very least, the activity visible on these scans correlates with conscious experiences such as craving. This evidence, while preliminary, cannot be ignored. Entire fields of scientific research are based on less.

On the question of stigma, the authors support the idea of considering addiction a moral failing. They believe the stigma against addicts is good, and that shame motivates people to stop using drugs. The correct answer here is “sort-of.” Stigma motivates drug and alcohol ABUSERS to get sober. When faced with the negative consequences of their drug use, the abuser can bring these negative consequences to bear on their decision-making. But stigma, or shame, or the threat of prison or death, will not work to change the behavior of addicts because the limbic brain equates drugs with survival at a very deep and unconscious level of brain processing. In light of this and the failure of the “consequence appreciating” areas of the cortex, the utility of stigma and punishment in the motivation of addicts is dubious. When craving kicks in, the drug comes first. The addict literally believes that the best way to stay out of jail is to get high (secure survival) now, and deal with the consequences later. This is the most fascinating and frustrating feature of addiction: negative consequences have no effect on the pattern of drug use. If you really are dealing with an addict, punishment doesn’t work.

As it stands in addiction medicine today, there is no way to tell the difference, not with definitive certainty, between the really bad drug abuser and the not so bad drug addict. The conflation of these two populations – abusers and addicts – creates much confusion. The promise of these neuroimaging scans is that they may someday be able to detect the minute differences in brain activity that differentiate the abuser from the actual addict.

In the meantime, we would do well to remember the long and painful history in medicine of labeling the behavior of people we didn’t like as “badness,” only later to learn something new about the way the brain or body works and realize that these behaviors were, in fact, symptoms – of a disease process. How do we know we are not making the same mistake again with addicts? The risk of being terribly wrong suggests caution. It is a strange specialty of medicine that uses shame as a therapeutic modality or stigmatizes patients to promote health. In fact, medicine’s contribution to the concept of justice lies in its ability to reveal the difference between those behaviors that are, in fact, symptoms, and those that are truly bad. Doctors cultivate an intuition – a “sixth sense” – that tells us: but for the disease process, the patient would not act this way. I get that feeling when I look at addicts.

Lastly, on the question of spiritual change the authors cite the experience of Jamie Lee Curtis as an example of how many addicts enter recovery. In Ms. Curtis’ case, she never went to treatment to get sober; rather she had a spiritual experience and relied solely on her attendance at A.A. meetings. But what got her sober? Was it the shame of some stigma or punishment hanging over her head (a stick)? Was it the reward of a promising career in film (a carrot)? Or was it the fact that she found something that was deeply, personally, emotionally meaningful - in her case, a relationship with God?

These deeply personally meaningful things – which will be individual to each person (“God as he/she understands Him”) – have the power to break the hold of craving. They are spiritual. They restore the function of the prefrontal cortex, and with it the addict’s power to choose meaningful things over drugs. The task of addiction treatment is to teach the addict stress coping tools to decrease their craving, while at the same time helping them find the one thing that is a little more meaningful (a little “higher in its power”) than drugs or alcohol. Or food, or sex, or gambling. A.A. does this nicely, but none of this comes to the patient overnight. Treatment that understands addiction as a disease can be indispensable as well.

So is addiction a disease? Yes. Do addicts need to take responsibility for managing their addiction? Certainly. But so do all patients. So do patients with multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia. The problem I have is in holding one group of patients more responsible than other groups of patients. Most people will take responsibility to the exact extent that they know how, or are supported. That is what good medicine is all about.

Kevin T. McCauley, M.D.

The Institute for Addiction Study

Park City, Utah

Her odd association with an ultra-conservative think thank (The American Enterprise Institute) notwithstanding, Dr. Satel’s monograph “Is Drug Addiction a Brain Disease?” is the best-articulated argument against the conceptualization of addiction as a disease (it can be found at http://www.eppc.org/publications/bookID.19/book_detail.asp). Likewise, Dr. Lillianfeld’s effort to expose semantic mistakes in psychology is commendable. However their views on addiction reveal fundamental mistakes regarding the nature of addiction and the experience of the addicted patient.

On the question of language, the authors claim that characterizing addiction as a brain disease appropriates language used to describe conditions such as multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia. Yes, and rightly so. Our modern concept of disease – the “Disease Model” – emerged from Germ Theory over a century ago, and evolved such that today it can be defined as a physical, cellular defect or lesion in a bodily organ or organ system that leads to the expression of signs and symptoms in the patient. This is a very rigorous standard for disease (it is also the standard demanded by Dr. Thomas Szasz, another opponent of the conceptualization of addiction as a disease).

For most of the last century, it has not been possible to fit addiction to this standard. That has changed. The organ involved in addiction is the limbic brain (specifically the ventral tegmentum and nucleus accumbens/extended amygdala). The defect is a stress-induced/genetically predisposed dysfunction of the limbic dopamine system (specifically a hedonic dysfunction – a broken “pleasure sense”). And the symptoms of greatest importance are 1) loss of control, 2) craving, and 3) persistent drug use despite negative consequences. Addiction meets the standard definition of disease better than multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia, two diseases whose pathophysiologies are far less elucidated. This is why medicine can claim, with confidence, that addiction is a disease.

On the question of personal agency and choice, the authors complain that calling addiction a “disease” undermines personal agency and our concept of free will. This is not, however, a problem with addiction. The standard definition of disease as it is used in medical practice today strips patients of their power of choice and hands that power to the doctor. In exchange, the patient gets to enter the sick role – a helpless, compliant role, and one relieved of responsibility. So the problem of addicts claiming that they have a disease and must be absolved of responsibility for their behavior is not a problem with addiction. It’s a problem with our standard definition of disease. Most of the authors’ trouble in calling addiction a disease stems not from whether or not addiction fits our standard definition of disease (it does), it stems from the problems inherent in the Disease Model itself.

As for choice, in addition to being a broken hedonic system in the brain, addiction is also a disorder of volition. Craving states cause a selective hypofunctionality of the prefrontal cortex. This is visible on neuroimaging scans such as functional MRI. The area of the brain of particular interest is the ventro-medial prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain that assesses future consequences. It is hard to underestimate the importance of these findings. They imply that choice is a variable quantity during some brain disease states. The exciting opportunity here is to figure out how choice really works. How is it realized in the brain? What are the conditions under which it best operates? And how do we set those conditions so that addicted patients can exercise free will according to their true values?

The authors may be correct in their assertion that these neurological scans may not mean all that their proponents say they do. But they do mean something. At the very least, the activity visible on these scans correlates with conscious experiences such as craving. This evidence, while preliminary, cannot be ignored. Entire fields of scientific research are based on less.

On the question of stigma, the authors support the idea of considering addiction a moral failing. They believe the stigma against addicts is good, and that shame motivates people to stop using drugs. The correct answer here is “sort-of.” Stigma motivates drug and alcohol ABUSERS to get sober. When faced with the negative consequences of their drug use, the abuser can bring these negative consequences to bear on their decision-making. But stigma, or shame, or the threat of prison or death, will not work to change the behavior of addicts because the limbic brain equates drugs with survival at a very deep and unconscious level of brain processing. In light of this and the failure of the “consequence appreciating” areas of the cortex, the utility of stigma and punishment in the motivation of addicts is dubious. When craving kicks in, the drug comes first. The addict literally believes that the best way to stay out of jail is to get high (secure survival) now, and deal with the consequences later. This is the most fascinating and frustrating feature of addiction: negative consequences have no effect on the pattern of drug use. If you really are dealing with an addict, punishment doesn’t work.

As it stands in addiction medicine today, there is no way to tell the difference, not with definitive certainty, between the really bad drug abuser and the not so bad drug addict. The conflation of these two populations – abusers and addicts – creates much confusion. The promise of these neuroimaging scans is that they may someday be able to detect the minute differences in brain activity that differentiate the abuser from the actual addict.

In the meantime, we would do well to remember the long and painful history in medicine of labeling the behavior of people we didn’t like as “badness,” only later to learn something new about the way the brain or body works and realize that these behaviors were, in fact, symptoms – of a disease process. How do we know we are not making the same mistake again with addicts? The risk of being terribly wrong suggests caution. It is a strange specialty of medicine that uses shame as a therapeutic modality or stigmatizes patients to promote health. In fact, medicine’s contribution to the concept of justice lies in its ability to reveal the difference between those behaviors that are, in fact, symptoms, and those that are truly bad. Doctors cultivate an intuition – a “sixth sense” – that tells us: but for the disease process, the patient would not act this way. I get that feeling when I look at addicts.

Lastly, on the question of spiritual change the authors cite the experience of Jamie Lee Curtis as an example of how many addicts enter recovery. In Ms. Curtis’ case, she never went to treatment to get sober; rather she had a spiritual experience and relied solely on her attendance at A.A. meetings. But what got her sober? Was it the shame of some stigma or punishment hanging over her head (a stick)? Was it the reward of a promising career in film (a carrot)? Or was it the fact that she found something that was deeply, personally, emotionally meaningful - in her case, a relationship with God?

These deeply personally meaningful things – which will be individual to each person (“God as he/she understands Him”) – have the power to break the hold of craving. They are spiritual. They restore the function of the prefrontal cortex, and with it the addict’s power to choose meaningful things over drugs. The task of addiction treatment is to teach the addict stress coping tools to decrease their craving, while at the same time helping them find the one thing that is a little more meaningful (a little “higher in its power”) than drugs or alcohol. Or food, or sex, or gambling. A.A. does this nicely, but none of this comes to the patient overnight. Treatment that understands addiction as a disease can be indispensable as well.

So is addiction a disease? Yes. Do addicts need to take responsibility for managing their addiction? Certainly. But so do all patients. So do patients with multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia. The problem I have is in holding one group of patients more responsible than other groups of patients. Most people will take responsibility to the exact extent that they know how, or are supported. That is what good medicine is all about.

Kevin T. McCauley, M.D.

The Institute for Addiction Study

Park City, Utah

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)